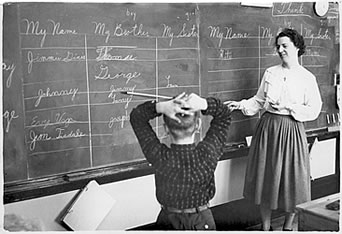

It is the bane of teachers: – pupils not remembering what we teach them, but more than that, remembering the wrong stuff instead. You think you’ve taught a memorable lesson and then the next day all they can talk about is the man’s funny glasses in the video you showed them. Teachers have to fight to hold onto pupils’ attention and get stuff to stick! It’s a huge tug of war with all sort of things: friends, last night’s TV show, the argument with a friend at playtime… the list is endless. If you’ve read Graham Nuthall’s truly wonderful book: The Hidden Lives of Learners, then you’ll also know that a lot of the time kids aren’t thinking or talking about what we want them to in lessons at all. This is why teaching is hard! But there’s hope! (As Basil Fawlty always said, ‘it’s the hope that gets to you’…)

Ever hopeful, I recently came across a paper entitled: How Seductive Details Do Their Damage: A Theory of Cognitive Interest in Science Learning by Shannon F. Harp and Richard E. Mayer.

This paper researches how additional information in the form of illustrations and photographs in science text books might hinder pupils’ learning. This got me to wondering about all the misplaced ‘seductive details’ there might be in my lessons, additional ‘stuff’ that clogs up pupils’ working memories and leads learning astray. Harp and Mayer’s research seems to resonate here…

To begin with, most lessons are formed around teaching a main idea or set of ideas, and by the end of the lesson we want pupils to have thought about these enough to make it stick – to have integrated this into their understanding – reformulating and expanding existing mental schemas. However, there’s much to prevent this and the concept of ‘seductive details’ (which might be considered no different from Sweller’s ‘extraneous content’) is one way to appreciate this:

Seductive details: “highly interesting and entertaining information that is only tangentially related to the topic but is irrelevant to the author’s intended theme.”

Here, I’m repositioning the author as the teacher, presenting and explaining new information in class. In the same way that Harp and Mayer describe the three processes learners use to remember the main ideas in a text, I’m basing this thought experiment on pupils using the same three distinct processes in order to ‘construct a coherent mental representation of the information’ we teach (1998:2). The processes for this are selecting, organising and integrating the information relating to the main idea.

Selecting: refers to paying attention to relevant pieces of information in the main idea or ideas. Here, for example, let’s imagine the main idea is that animals can be grouped into three different groups depending on their types of diet. Through everything that a learner hears or sees in the lesson, this is the information they need to select and focus on.

Organising: refers to building internal connections among selected pieces of information that are presented or explained, for example, that there are different types of animals with different types of teeth and they can be predators and, or prey.

Integrating: refers to building external connections between incoming information and prior knowledge. For example, that cats have sharp pointy teeth, they chase birds and other little animals and eat meat in the form of cat food.

So now – how do seductive details damage this processing of a main idea? One thing to note first is that seductive details often require less mental effort or attentional focus to process so they are easier to understand than the main idea. The mind operates along on what I think of as, ‘the path of least resistance,’ or as Daniel Willingham suggests, it prefers memory to thinking. So seductive details are just easier and less effortful, that’s part of what makes them seductive. It’s like having to choose between walking to work in the rain, or getting a lift in a warm car; most people will choose the car as it’s easier and more comfortable.

Following this, there are three premises Harp and Mayer discuss in regard to how seductive details might damage these types of processing. Here, I’ve thought about how they might unfold in teaching:

Distraction hypothesis – in constructing a coherent representation of the information taught, a learner must first ‘select’ the information to focus on. Seductive details here literally ‘seduce’ a learner’s selective attention away from the main idea. It’s a bit like going to the salad bar at a café, then noticing the bowl of crisps at the side… if you’re like me, my selective attention is pulled away from the green stuff.

Examples: In our lesson about types of animals and how they are grouped into carnivores, herbivores and omnivores according to their diets….

- An image of a cute kitten wearing a collar with a bell is used. Rather than thinking about the characteristics of a carnivore, the learner thinks about why the kitten has a collar with a bell and what the bell might sound like.

- While giving an explanation, the teacher inadvertently mentions that her cat, a carnivore, is very fussy and always leaves his food. The learner then thinks about the teacher’s fussy cat and what happens to all the leftover food. It’s easier to let your mind wonder about left over cat food than complicated terms for different types of animals, right?

Like this, seductive details can prevent the learner selecting the right information to focus on in order to understand the main idea. Notably, we often try to guide learners to select the information to process by telling children to pay attention to the main idea, but Harp and Mayer’s research showed that for text at least, this did not reduce the affect of the seductive details – learners still got distracted and went off on their mental tangents. It’s because they’re seductive! It’s like when people say, ‘don’t look’ and all you do is look – so teachers saying ‘pay attention’ doesn’t decrease the seduction.

Disruption hypothesis– here seductive details interrupt transition from one main idea to the next which interferes with the organisation of information involved in the main idea. Learners need to construct a clear mental model of the main idea that is linked to other related concepts in their own mental schemas. For example, in order to learn the concepts of carnivore, herbivore and omnivore, we also teach children about types of teeth, predators and prey which leads to learning about simple food chains. Seductive details can then disrupt the links learners need to make between concepts that formulate mental models of the main idea. The result is that learners then interpret each new piece of information separately instead of being as part of a chain of information. This interruption then hinders schema building. It’s a bit like building a jigsaw, but there’s pieces from another jigsaw mixed in and you’ve lost the lid of the box too.

Example: After presenting the concept of carnivore, omnivore and herbivore, the teacher plays an ‘entertaining’ cartoon clip about cats chasing mice, and mice eating seeds before turning to the idea of different types of teeth. For some children, this might break the link between what animals eat and types of teeth so they are unable to build a coherently organised mental model of how diet and teeth are linked.

Diversion hypothesis– seductive details here activate inappropriate prior knowledge which then hinders the interpretation of information into a learner’s schema understanding. Here the learner builds a mental model not around the main idea, but instead around those seductive details. Those entertaining additions, ‘prime the activation of inappropriate prior knowledge as the organising schema for the lesson’ (1998:3).

Example: The teacher uses an exciting image of a shark attacking a fish to talk about carnivores resulting in the learner thinking about the time they were scared swimming in the sea. They are misled into relating that image to their prior learning about the danger of certain carnivores. The information about diet and types of teeth then becomes secondary information and the learner regards this as only supporting information rather than the main idea.

To conclude, I’ve borrowed this idea of seductive details and thought about how this might be applied to presenting and explaining. Unlike Harp and Mayer, I haven’t tested my ideas at all and have to all intense and purposes, lifted a piece of research about reading and thought about what that might mean for presenting and explaining.

This is certainly not to say that teachers shouldn’t use anecdotes, interesting pictures or videos when they present or explain. However, as Harp and Mayer suggest, ‘one way to discourage inappropriate schema activation is to delay the introduction of seductive information until after the reader has processed the important material. Another way is simply not to introduce seductive details at all (1998:19). So, if this does have resonance in how we present or explain, then perhaps leaving that entertaining video, or that story about your cat to the end might help make it all stick. Here’s hoping!

Let me end with Harp and Mayer’s challenge for us all: ‘to find a way to present science lessons in a way that is interesting, without resorting to the use of entertaining but irrelevant details,’ (1998:20).

I’m up for it!